Where “I Bought It For The Dividend” Went Wrong

In early 2017, I warned investors about the “I bought it for the dividend” investment thesis. To wit:

“Company ABC is priced at $20/share and pays $1/share in a dividend each year. The dividend yield is 5%, which is calculated by dividing the $1 cash dividend into the price of the underlying stock.

Here is the important point. You do NOT receive a ‘yield.’

What you DO receive is the $1/share in cash paid out each year.

Yield is simply a mathematical calculation.“

At that time, the article was scoffed at because we were 8-years into an unrelenting bull market where even the most stupid of investments made money.

Unfortunately, the “mean reversion” process has taken hold, which is the point where the investment thesis falls apart.

The Dangers Of “I Bought It For The Dividend”

“I don’t care about the price, I bought it for the yield.”

First of all, let’s clear up something.

In January of 2018, Exxon Mobil, for example, was slated to pay an out an annual dividend of $3.23, and was priced at roughly $80/share setting the yield at 4.03%. With the 10-year Treasury trading at 2.89%, the higher yield was certainly attractive.

Assuming an individual bought 100 shares at $80 in 2018, “income” of $323 annually would be generated.

Not too shabby.

Fast forward to today with Exxon Mobil trading at roughly $40/share with a current dividend of $3.48/share.

Investment Return (-$4000.00 ) + Dividends of $323 (Yr 1) and $343 (Yr 2) = Net Loss of $3334

That’s not a good investment.

In just a moment, we will come and revisit this example with a better process.

There is another risk, which occurs during “mean reverting” events, that can leave investors stranded, and financially ruined.

Dividend Loss

When things “go wrong,” as they inevitably do, the “dividend” can, and often does, go away.

- Boeing (BA)

- Marriott (MAR)

- Ford (F)

- Delta (DAL)

- Freeport-McMoRan (FCX)

- Darden (DRI)

These companies, and many others, have all recently cut their dividends after a sharp fall in their stock prices.

I previously posted an article discussing the “Fatal Flaws In Your Financial Plan” which, as you can imagine, generated much debate. One of the more interesting rebuttals was the following:

“If a retired person has a portfolio of high-quality dividend growth stocks, the dividends will most likely increase every single year. Even during the stock market crashes of 2002 and 2008, my dividends continued to grow. The total value of the portfolio will indeed fluctuate every year, but that is irrelevant since the retired person is living off his dividends and never selling any shares of stock.

Dividends usually go up even when the stock market goes down.”

This comment is the basis of the “buy and hold” mentality, and many of the most common investing misconceptions.

Let’s start with the notion that “dividends always increase.”

When a recession/market reversion occurs, the “cash dividends” don’t increase, but the “yield” does as prices collapse. However, your INCOME does NOT increase. There is a risk it will decline as companies cut the dividend or eliminate it.

During the 2008 financial crisis, more than 140 companies decreased or eliminated their dividends to shareholders. Yes, many of those companies were major banks; however, leading up to the financial crisis, there were many individuals holding large allocations to banks for the income stream their dividends generated. In hindsight, that was not such a good idea.

But it wasn’t just 2008. It also occurred dot.com bust in 2000. In both periods, while investors lost roughly 50% of their capital, dividends were also cut on average of 12%.

While the current market correction fell almost 30% from its recent peak, what we haven’t seen just yet is the majority of dividend cuts still to come.

Naturally, not EVERY company will cut their dividends. But many did, many will, and in quite a few cases, I would expect dividends to be eliminated entirely to protect cash flows and creditors.

As we warned previously:

“Due to the Federal Reserve’s suppression of interest rates since 2009, investors have piled into dividend yielding equities, regardless of fundamentals, due to the belief ‘there is no alternative.’ The resulting ‘dividend chase’ has pushed valuations of dividend-yielding companies to excessive levels disregarding underlying fundamental weakness.

As with the ‘Nifty Fifty’ heading into the 1970s, the resulting outcome for investors was less than favorable. These periods are not isolated events. There is a high correlation between declines in asset prices, and the dividends paid out.”

Love Dividends, Love Capital More

I agree investors should own companies that pay dividends (as it is a significant portion of long-term total returns), it is also crucial to understand that companies can, and will, cut dividends during periods of financial stress.

It is a good indicator of the strength of the underlying economy. As noted by Political Calculations recently:

Dividend cuts are one of the better near-real-time indicators of the relative health of the U.S. economy. While they slightly lag behind the actual state of the economy, dividend cuts represent one of the simplest indicators to track.

In just one week, beginning 16 March 2020, the number of dividend cuts being announced by U.S. firms spiked sharply upward, transforming 2020-Q1 from a quarter where U.S. firms were apparently performing more strongly than they had in the year-ago quarter of 2019-Q1 into one that all-but-confirms that the U.S. has swung into economic contraction.

Not surprisingly, the economic collapse, which will occur over the next couple of quarters, will lead to a massive round of dividend cuts. While investors lost 30%, or more in many cases, of their capital, they will lose the reason they were clinging on to these companies in the first place.

You Can’t Handle It

EVERY investor has a point, when prices fall far enough, regardless of the dividend being paid, they WILL capitulate, and sell the position. This point generally comes when dividends have been cut, and capital destruction has been maximized.

While individuals suggest they will remain steadfast to their discipline over the long-term, repeated studies show that few individuals actually do. As noted just recently is “Missing The 10-Best Days:”

“As Dalbar regularly points out, individuals always underperform the benchmark index over time by allowing “behaviors” to interfere with their investment discipline. In other words, investors regularly suffer from the ‘buy high/sell low’ syndrome.”

Behavioral biases, specifically the “herding effect” and “loss aversion,” repeatedly leads to poor investment decision-making. In fact, Dalbar is set to release their Investor Report for 2020, and they were kind enough to send me the following graphic for investor performance through 2019. (Pre-Order The Full Report Here)

These differentials in performance can all be directly traced back to two primary factors:

- Psychology

- Lack of capital

Understanding this, it should come as no surprise during market declines, as losses mount, so does the pressure to “avert further losses” by selling. While it is generally believed dividend-yielding stocks offer protection during bear market declines, we warned previously this time could be different:

“The yield chase has manifested itself also in a massive outperformance of ‘dividend-yielding stocks’ over the broad market index. Investors are taking on excessive credit risk which is driving down yields in bonds, and pushing up valuations in traditionally mature companies to stratospheric levels. During historic market corrections, money has traditionally hidden in these ‘mature dividend yielding’ companies. This time, such rotation may be the equivalent of jumping from the ‘frying pan into the fire.’”

The chart below is the S&P 500 High Dividend Low Volatility ETF versus the S&P 500 Index. During the recent decline, dividend stocks were neither “safe,” nor “low volatility.”

But what about previous “bear markets?” Since most ETF’s didn’t exist before 2000, we can look at the “strategy” with a mutual fund like Fidelity’s Dividend Growth Fund (FDGFX)

As you can see, there is little relative “safety” during a market reversion. The pain of a 38%, 56%, or 30%, loss, can be devastating particularly when the prevailing market sentiment is one of a “can’t lose” environment. Furthermore, when it comes to dividend-yielding stocks, the psychology is no different; a 3-5% yield, and a 30-50% loss of capital, are two VERY different issues.

A Better Way To “Invest For The Dividend”

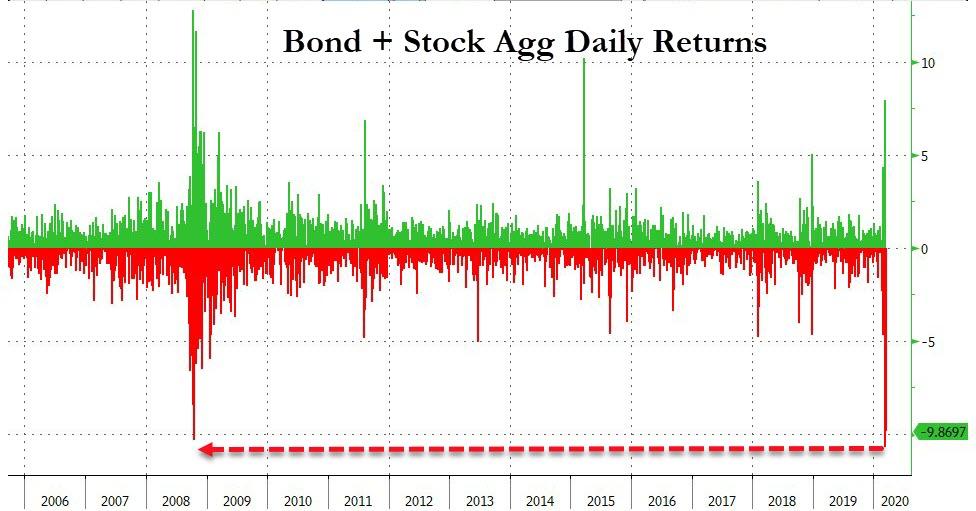

“Buy and hold” investing, even with dividends and dollar-cost-averaging, will not get you to your financial goals. (Click here for a discussion of chart)

So, what’s the better way to invest for dividends? Let’s go back to our example of Exxon Mobil for a moment. (This is for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation.)

In 2018, Exxon Mobil broke below its 12-month moving average as the overall market begins to deteriorate.

If you had elected to sell on the break of the moving average, your exit price would have been roughly $70/share. (For argument sake, you stayed out of the position even though XOM traded above and below the average over the next few months.)

Let’s rerun our math from above.

- In 2018, an individual bought 100 shares at $80.

- In 2019, the individual sold 100 shares at $70.

Investment Return (-$1000.00 ) + Dividends of $323 (Yr 1) and $343 (Yr 2) = Net Loss of $334

Not to bad.

Given the original $8,000 investment has only declined to $7,666, the individual could now buy 200 shares of Exxon Mobil with a dividend of $3.48 and a 9.3% annual yield.

Let’s compare the two strategies.

- Buy And Hold: 100 shares bought at $80 with a current yield of 4.35%

- Risk Managed: 200 shares bought at $40 with a current yield of 9.3%

Which yield would you rather have in your portfolio?

In the end, we are just human. Despite the best of our intentions, emotional biases inevitably lead to poor investment decision-making. This is why all great investors have strict investment disciplines they follow to reduce the impact of emotions.

I am all for “dividend investment strategies,” in fact, dividends are a primary factor in our equity selection process. However, we also run a risk-managed strategy to ensure we have capital available to buy strong companies when the opportunity presents itself.

The majority of the time, when you hear someone say “I bought it for the dividend,” they are trying to rationalize an investment mistake. However, it is in the rationalization that the “mistake” is compounded over time. One of the most important rules of successful investors is to “cut losers short and let winners run.”

Unfortunately, the rules are REALLY hard to follow. If they were easy, then everyone would be wealthy from investing. They aren’t because investing without a discipline and strategy has horrid consequences.